Karel Doormanstraat 278

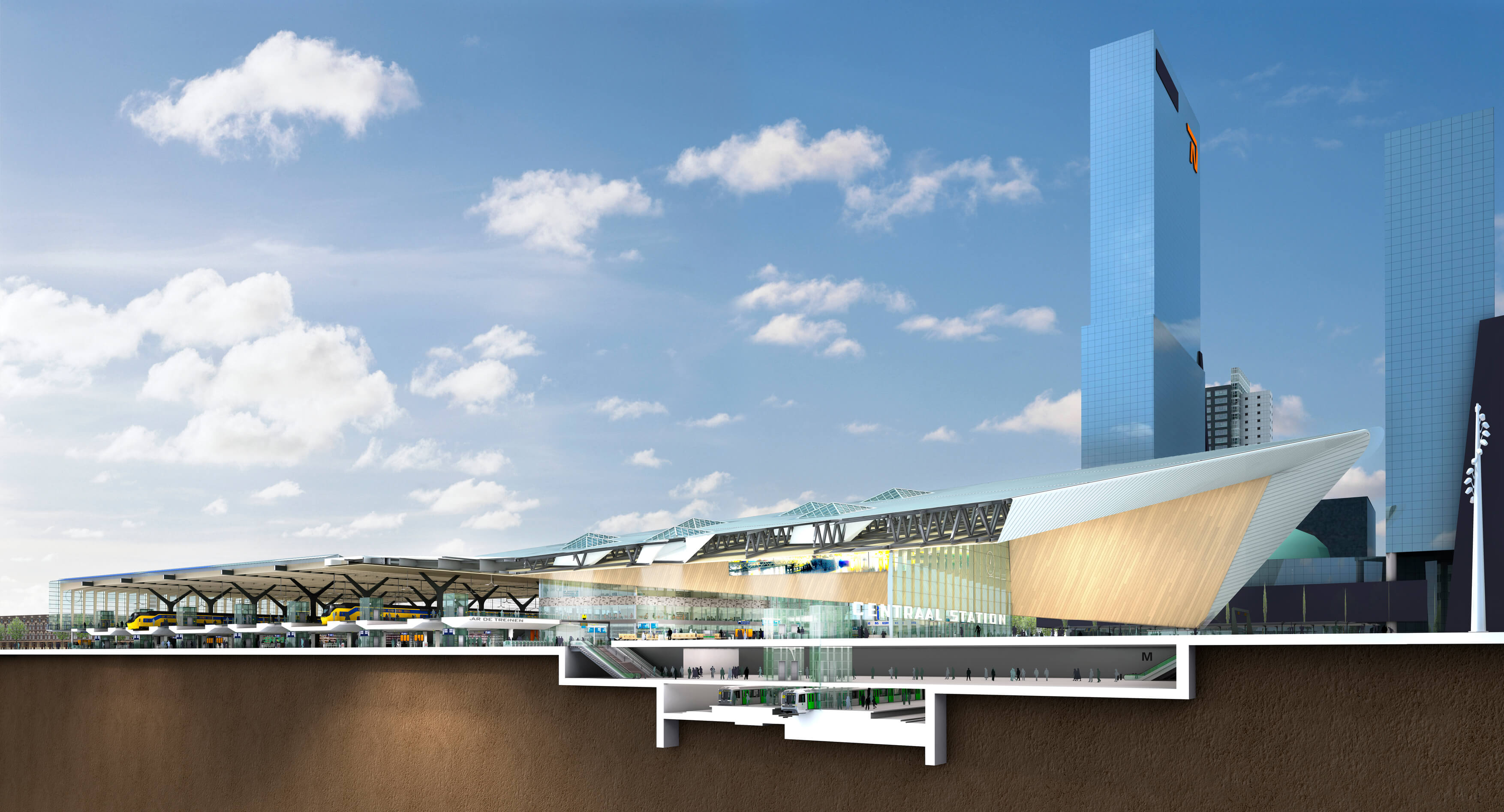

Dreamhouse – New Modernism with Suitable Chicness helps rejuvenate the Lijnbaan

With Dreamhouse, the new life that lies dormant in the old Modernism of the Lijnbaan has been extrapolated. A new Modernism, with a variegation of volumes and nuances of colour and light, seems to have been the right catalyst to reawaken the Lijnbaan’s élan.

The skilfully renovated building, housing jewellers Schaap en Citroen and fashion retailer COS on the corner of Karel Doormanstraat and Kruiskade, is the result of a well-balanced design that is based on both past intentions and present ambitions. Optimistic investment has brought about sparkle where decline had become apparent. Within a strategy of sustainable renewal, closed off facades and shop fronts have been reopened with architectural ingenuity.

In order to appreciate the value of Dreamhouse’s architectural feat, we must first take a look at the Lijnbaan and Martin’s Tearoom. The Lijnbaan complex in Rotterdam is currently in a stage of uncertainty, alternatively being the embodiment of a faded dream for the future and being the dream of a new future. Five years ago the Lijnbaan Shopping Centre was listed as a Grade 1 heritage site (rijksmonument) because the retail promenade, building blocks and expedition lanes were considered to be “of historical value as an essential and exemplary model of the post-war 1940-1958 era.” The official listing notes, among other reasons, its “characteristic Modernist architecture” and makes an expedient distinction between the ‘fixed’ components of the site and the changeable retail fronts and interiors. This differentiation raises the question of how tarnishing the consequences of change can be, or how exciting.

After starting out in 1955 as Martin’s, a flourishing tea room and restaurant, the building’s non-fixed parts underwent various transformations, each one more damaging than the previous. Designed by the then well-known architectural practice Van den Broek en Bakema with an audacious light installation on the roof, Martin’s expensive hardwood facade advertised the wonderfully new “selfservice”, imported from the admired United States of America, the land of endless opportunities that had won the war. The longing for all that was new reflected the optimism concurrent with rising welfare. The 1971 transformation into a furniture store involved closing off the second floor facade with cladding and lowering the overhang in line with the canopies of the other Lijnbaan shops, which in fact contradicts its primary design scheme. Further encroachments were undertaken in 1998, ironically under the name ‘Dreamhouse’ – though which at least evoked something of the spirit of the past. A transformation to clothing store with café ultimately lead to ‘Dream: your favorite steakhouse’, complete with an inappropriate partial faux-prairie hut above the entrance.

So much for the history of the Lijnbaan and the decline of Martin’s, now for the rebirth of a remarkable structure. As part of a broader post-war reconstruction plan (Rotterdam was effectively flattened in 1940), the three-storey corner block is part of a series of distinctive buildings in and around the Lijnbaan, including among others the former cinemas Thalia and Lumière, now respectively De Beurs and Fitness First together with Hugo Boss. These are the result of a conscious effort to increase the urban vitality of the Lijnbaan. Taller than the horizontal retail spaces, they act architecturally as a pivoting point between the shops and the higher residential blocks that flank the shopping promenade. KAAN’s design ties in with these circumstances.

The original intentions that underpin the subtleties found in the Lijnbaan area and that express the ambitions aimed for by Martin’s, were a source of inspiration. Yet inspiration alone does not provide a concrete architectural solution to a delicate design task. The cheerful Modernism of the post-war period is to contemporary modernism as near-clear skies are to a richly variegated canopy of clouds. The well-known Schokbeton (compacted concrete), which was considered attractive at the time, has lost its charm and contemporary construction is technically and organically very different to that of the early 1950s. The question was which spatial interventions and which materials and colours would lead to a rejuvenated Lijnbaan and add a new shine to its character?

The answer is new modernism: still focused on functionality, but now discreetly distinguished and reservedly chic; no crazy shapes or bright colours, nor any pompous urbanity. Rectangular volumes have been stacked in balanced proportions over three floors on top of existing columns, and display a subtle differentiation of materials, window openings, colours and other details. The stacking presents unity in diversity. The first storey projects markedly, and as such clearly echoes the ‘millstone ruff’ of offices in the surrounding residential flats of The Cityhouse by renowned architects Maaskant en Van Tijen. The facade of the overhang is still accented by windows. Perpendicular to the largely glass sheet windows are fixed vertical slats – deep, thin and cleanly lined within a framework.

The slats and their encasement prove the existence of a geometric Baroque for they manipulate the view and play of light just as traditional Baroque does, but now without the twists and curves; it is simply straight-edged. Apart from their rhythmic synchronisation with the protruding balconies on the facade of the opposite flats, they have a surprising optical effect. Seen from the side, the overhang appears quite closed. Seen straight on, the building emerges as a show-box and affords an unobstructed view inside. By extruding (pressing through a mould) and anodising the aluminium, the slats acquired their knife-sharp edges and pearl grey colour. They allow a soft reflection of light and colours from inside out and from the sun, clouds and trees outside in. For those willing to see it, it is a timeless delight.

Architect: KAAN Architecten

Client: Manhave Vastgoed

Contractor: MBM Advies

Photography: Sebastian van Damme

Name of the building

Karel Doormanstraat 278

Client, architect or builder

Architect: KAAN Architecten, Opdrachtgever: Manhave Vastgoed, Bouwer: MBM Advies